There has rightly been a lot of attention given recently to the centenary of the birth of Pope John Paul II, who was born in 1920, and changed the face of global Catholicism over the course of his long and consequential pontificate. One of my favorite of his writings is Centesimus Annus (“The 100th Year”) which like Quadragesimo Anno (40 years), Mater et Magister (70 years), Octogesima Adveniens (80 years), and Laborem Exercens (90 years), all marked anniversaries of Pope Leo XIII’s groundbreaking 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum. Official Vatican texts often draw their titles from creative readings of their opening words– e.g. Humanae Vitae (“Of Human Life”), Ex Corde Ecclesiae (“From the Heart of the Church”), Spe Salvi (“In Hope We Were Saved”). So the allusion in many of these “anniversary” texts is explicit.

Rerum Novarum, whose opening words are tellingly either translated as “Of New Things” or “Of Revolutionary Change,” explores the church’s commitment to justice in a world experiencing the aftereffects of the industrial revolution and contemporary urbanization, and is widely considered the foundational text of the modern Catholic Social Teaching movement.

In my current summer course (which was originally supposed to have been taught in Rome but has been moved online), I recently provided a list of optional themes for one of the assignments and told my graduate students to select one. One read:

“Serve as an unofficial ghostwriter and draft the first five pages for Pope Francis of a new social encyclical which could be titled Post Centum Triginta (“After 130 Years”) marking next year’s anniversary of Rerum Novarum. It should deal with one or multiple pressing issues of our day and how the mission of Christian witness and commitment to justice should inform our response in a globalized world.”

I have no idea whether the Holy Father is in fact planning to promulgate such a document. But if he is, he should without question reach out to my lay graduate students studying for degrees in pastoral theology, spirituality, counseling for ministry, and social justice. Because, as usual, their diagnoses and prescriptions for the church, academy, and world in our times taught me more than I present in my sometimes rambling lectures to them.

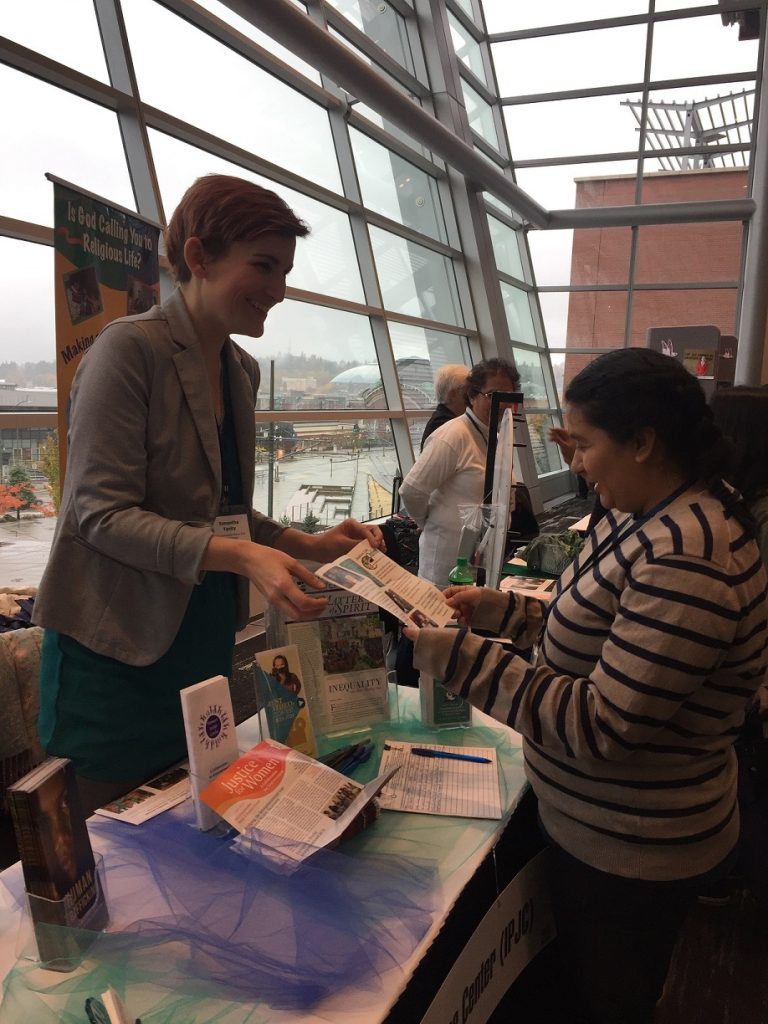

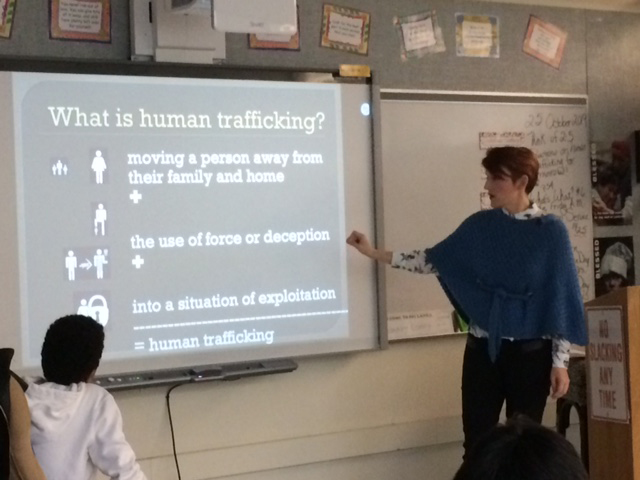

Concerns about racism, human trafficking, and immigration issues appeared often, as did the ecological crisis and economic systems of commodification. Secularism and partisan division in politics and church life are seen as metastasizing throughout our contemporary world. For many, wintry seasons where evangelization, ecumenism, and dialogue have suffered from chilling effects after the springtime of new hopes in the 1960’s and 1970’s marked our era, as did a general lament for the lack of bold witness to the wider culture on things like child protection, wealth inequality, and honest historical appraisals of the church’s many missteps. The need for interdisciplinary conversations especially around the natural and social sciences, healthcare advances, and theological ethics was mentioned repeatedly. And of course, the consequences of COVID and social distancing were probably more at the front of students’ minds than they will (hopefully) be if I revisit this assignment in future semesters.

One reality that was proffered consistently was the ongoing thirst for solidarity and subsidiarity, as people are parched to connect with one another and to have their voices heard – whether in an increasingly divided society or a still-too-clerical church. Of course, some exclusion is necessary in life, there are evils that the church can never endorse and still claim to be authentic to itself and its Lord, though even these need to be studied assiduously. But the realities of our day continue to call for a more inclusive and dialogical church, demanded precisely through the voices of mostly lay men and women who are studying these disciplines with me and so many others like me, often at a significant sacrifice of time outside of other responsibilities, limited precious energy that could easily be spent elsewhere, and – undoubtedly – serious personal financial cost. I can only wish that Pope Francis could be personally as inspired by these students as I unfailingly am. If he and future church leaders were to listen to their insights, as I am blessed to do day in and day out, I am convinced that the next 130 years of Christian life would undoubtedly be better than the previous ones have been.