Sarah Gregory

Executive Content Editor

Loyola University Chicago School of Law, J.D. 2018

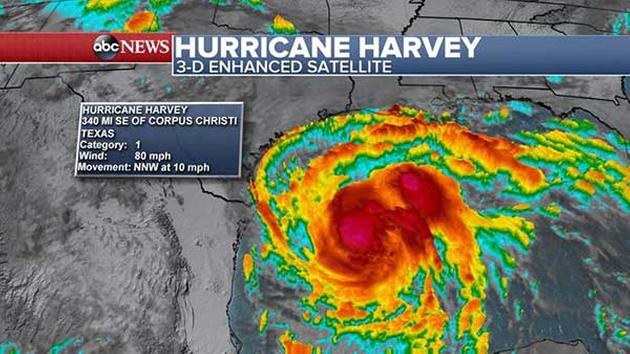

Though the rain has stopped falling, Houston is still dealing with the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, one of the largest and most destructive rainfall events on record. Healthcare providers in particular find themselves struggling to keep up with various health problems caused by the flooding itself, on top of getting life-sustaining care to individuals with chronic or preexisting conditions. Crises like Harvey create serious problems for the delivery of care, but also for regulating it—circumstances are so uniquely devastating that standards can feel like barriers to necessary medical attention. And when family and friends are desperate to know if their loved one is out of danger, even the right of privacy seems negligible.

However, natural disasters and emergency events shouldn’t be used as an excuse to regulate away protections individuals depend on, such as the privacy and confidentiality of their personal information. Regulators must be careful when determining how to respond in a crisis—overreaching for the sake of bringing relief or under-regulating for flexibility can leave the public high and dry when the floodwaters recede.

Waiving the HIPAA Privacy Rule

The communal good of public health has always been an implicit factor in the equation of healthcare privacy. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule, doesn’t require authorization to disclose protected health information to a public health or disaster relief authority, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the Red Cross. It’s a minor concession to public health in a set of regulations focused on preserving individual privacy. However, in 2004 the Project Bioshield Act expanded the power of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) in this area, authorizing the Secretary to waive parts of the Privacy Rule when a state of emergency or disaster has been declared.

Declaring a public health emergency empowers the Secretary to take certain steps to relieve the regulatory burden on providers and ensure individuals affected receive emergency care. In conjunction with the Bioshield Act, section 1135 of the Social Security Act allows the Secretary to waive or modify certain Medicare, Medicaid, and CHIP requirements—including some aspects Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule.

The mechanism of waiving the HIPAA Privacy Rule in response to a public health emergency is rarely exercised. Though HHS has clarified HIPAA requirements in relation to emergencies like Ebola and the Pulse nightclub shooting in Orlando, a true blanket 1135 waiver has not been invoked since Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

However, on August 28, 2017, pursuant to the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, President Trump declared that a major disaster exists in the State of Louisiana, retroactive to August 27, 2017. Also on August 28, 2017, Secretary Tom Price declared a public health emergency in Texas and Louisiana in response to Hurricane Harvey. Under Section 1135, HHS could and did respond by issuing a blanket waiver of sanctions for violating certain provisions of the Privacy Rule. Providers in Louisiana and Texas will not face penalties for violating the following requirements:

- The requirements to obtain a patient’s agreement to speak with family members or friends involved in the patient’s care

- The requirement to honor a request to opt out of the facility directory

- The requirement to distribute a notice of privacy practices

- The patient’s right to request privacy restrictions

- The patient’s right to request confidential communications

The waiver only applies in the emergency area, and for the emergency period identified in the public health emergency declaration (i.e., Texas and Louisiana) and to hospitals that have instituted a disaster protocol. The allowance lasts only 72 hours from the time the hospital implements its disaster protocol—after that window, the Privacy Rule returns in full force.

The purpose of the Privacy Rule waiver is clear. For the first three days after a major threat to health and well-being, a healthcare provider may care for patients first and worry about administrative burdens second. A doctor can assure loved ones the patient is all right without a meticulously crafted and signed HIPAA authorization form; the nursing staff can focus on emergency triage, and not distributing a notice of privacy practices. The waiver is compassionate but effective—a recognition of the priorities that would likely take precedence with or without HHS’s permission.

Balancing the needs of privacy and effectiveness

The limited nature of the HIPAA Privacy Rule waiver and the rarity of its use keeps it from attracting too much criticism from privacy advocates. However, where the HIPAA Privacy Rule waiver targets protected health information and the procedures of providers, other regulations look to general personally identifiable information that collected and circulated. If the 1135 waiver is a brief, clearly-defined window where relief efforts take precedence over privacy, then regulations and laws protecting privacy can be fuzzy and badly-defined.

It is not as though the intention isn’t present. The National Incident Management Guide, for instance, put out through the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, explicitly identifies the need for a comprehensive information management system, where necessary information is shared among appropriate personnel. “[Information and Intelligence] should also work together to protect personally identifiable information, understanding the different combination of laws, regulations, and other mandates under which various local, state, tribal, territorial, insular area, and Federal agencies operate.” Yet at the state level, this takes different forms. Illinois, for instance, relies on the American Red Cross’ Safe and Well site, a centralized registry for survivors to voluntarily post their information and affirm their safety. Searching the registry requires a name, as well as a phone number or address, which serves as a soft stopgap to strangers poring over lists of victims. Beyond the registry, the Illinois Emergency Operations Plan (IEOP) states that all other “confidential personal information” provided to the Red Cross by disaster victims or emergency workers cannot be shared without explicit consent of the individual.

Is this enough? There’s no indication of whether HIPAA’s protected health information is also “confidential personal information”—a term not defined within the IEOP. Instead, interpreters must turn to another statute entirely for a working definition. Additionally, there is no guidance offered on how “explicit consent” should be given, whether it is a blanket permission or authorization has to be given for every fact. Even though the Safe and Well site requires entries in multiple fields to search the registry, the required information is hardly secure or personal. A quick google search will reveal addresses and names, even phone numbers. But requiring something a confidential Social Security Number would defeat the point of the registry entirely. While the IEOP addresses responses, mobilization, and ownership of various emergency response actions, it leaves privacy in uncertain terms.

There may be no perfect system for safeguarding protected health information and confidential personal information in a crisis, especially one of such devastating scale as Harvey. However, being fuzzy on who must secure what authorizations when, for what, adds further chaos and uncertainty to an already unstable situation.

UPDATED as of 9/8/17 to note that HHS has issued a Section 1135 waiver for Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands in light of Hurricane Irma.