Monopoly is one of the most well-known and iconic board games. According to Hasbro, eight out of ten people fight while playing Monopoly. What many people don’t know is the true story behind the creation and ownership of Monopoly. The story involves a fight over the intellectual property (“IP”) rights of the game.

The story starts with a female inventor by the name of Lizzie Magie. Magie patented her invention, “The Landlord’s Game,” in 1904. “The Landlord’s Game,” through a series of evolutions, later became the game we know and love as Monopoly. Magie lost credit as an inventor, until a trademark infringement dispute in 1973 brought her contribution and story to light. Monopoly’s origin story highlights the limits of IP protection and the historical unequal treatment of women inventors.

Magie’s Invention – “The Landlord’s Game”

Lizzie Magie was born in 1866, and she worked as a stenographer and a typist. Magie was a supporter of Georgism. Based on the ideas of economist Henry George, Georgism focuses on the idea of a single tax. Specifically, it emphasizes that the only tax that should be imposed is on the unimproved value of land.

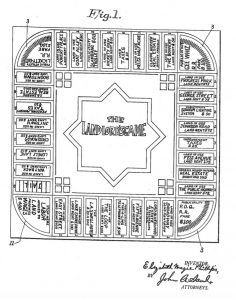

Magie sought to spread her Georgist views more widely by creating a board game called “The Landlord’s Game.” The game included two sets of rules: one monopolist and one anti-monopolist. The goal in the monopolist set was to buy up all the property and drive opponents into bankruptcy. In the anti-monopolist set, utilities were not taxed, and all rent was paid to a public treasury, not a private property owner. Magie hoped that the game would illustrate that the anti-monopolist approach was the morally right choice. In the game there was a designated banker, as well as paper cash, houses, deeds, and the famous “go to jail” space. Sound familiar?

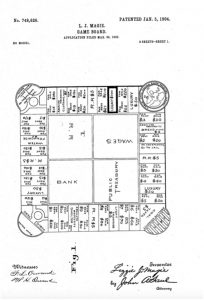

Magie was granted US patent no. 748626 on January 5th, 1904 for “The Landlord’s Game. At this time, women owned only 1% of patents. Both social and historical factors contributed to few women inventors being recognized. Historically, women did not have the same opportunities as men to learn technical skills because of discrimination in education. Additionally, woman faced challenges when it came to property ownership and engaging in business contracts. Women’s inability to own property and sign contracts was a major restriction on their financial and legal independence, which made it hard for them to secure and own patents.

After failing to find a publisher for her game, Magie self-published it in 1906. However, the game did not sell many copies. Though the exclusivity that comes with patents can help inventors achieve commercial success, such success is not guaranteed. The purpose of the patent system has multiple parts, and it’s more straightforward than many people think.

The Purpose of the Patent System

The patent system is designed to incentivize innovation by granting inventors exclusive rights to their inventions for a set period of time. Specifically, patent owners, including inventors, have the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing their patented invention during the lifetime of the patent. The term of protection granted by a patent typically lasts for 20 years from the date the patent application was filed. Once the patent expires, so too do the patent owner’s exclusive rights. This time limitation rewards inventors without granting them an indefinite “monopoly” of their own.

A violation of any of these exclusive rights is referred to as patent infringement. In other words, if someone is either making, selling, using, or importing a product that contains all of the elements as described in a patent without permission, they are infringing. In such a case, an inventor can sue the alleged infringer in court. If the inventor is successful in proving their case, the court will likely force the infringer to stop the infringing activity. Additionally, courts will often impose some sort of monetary damages to compensate the patent owner for the infringement.

Such a suit can only be brought for infringing activity that occurs within the term of the patent. Once the patent expires, it is no longer enforceable. In other words, if a person were to make, sell, use, or import a product that contains all of the elements of an expired patent, they would not be infringing.

This limited term can also indirectly mean that the identity of the original inventor of an invention can be lost over time. This is particularly true when subsequent changes and improvements fail to give credit to the original inventor, which is what happened to Lizzie Magie. Not everything can be patented, however, and the limitations on what is patentable are important to understand to see how these later changes and improvements can be made and even patented themselves.

Patentability and the 1904 Patent

An invention must meet certain criteria in order to be eligible for patent protection. First, the invention must cover patentable subject matter (“PSM”). PSM is based in statutory and common law exclusions. Things that are not PSM are: abstract ideas (like algorithms), laws of nature, and natural or physical phenomena.

Games can be difficult to patent because they can often involve abstract ideas. However, this was not the case with Magie’s “The Landlord’s Game.” Madie was not simply trying to claim a broad idea or concept. Instead, she was claiming the physical layout of the game board and the pieces. Therefore, the game easily passed the PSM requirement.

The next requirement for patentability is that the invention must also be useful. This requirement is relatively easy to meet, as long as the invention has at least one substantial and credible use that works. “The Landlord’s Game” served multiple uses. The game served as a source of entertainment. It also had an educational aspect to it, which was intended to educate players about economic theories. Therefore, Magie’s invention passed this (low) bar as well.

Next, “The Landlord’s Game” must have been new in order to be patented. This essentially means if there was a single existing product or publication with the exact same details as Magie’s game, her invention would not be new and thus not patentable. However, Madie’s invention was unique for its time. Many board games used a linear path that players would follow, while hers involved a circular path. Magie’s invention was new because it was unlike games that existed at the time. Thus, Magie’s game was sufficiently “new” for purposes of patent protection.

Finally, Magie’s invention must have been nonobvious in order to be patented. Nonobviousness is similar, yet distinct from the “new” requirement. In evaluating nonobviousness, multiple existing products and publications can be considered at the same time. If at the time of the invention, because of existing products or publications, the invention would be obvious to a person of ordinary skill in the art (POSITA), the invention is obvious and cannot be patented. A POSITA is someone who is presumed to know and understand the relevant art (existing products and publications) at the time of the invention. Because Magie’s game was so unique at the time she invented it, her invention was not obvious, and she was able to get her patent!

The 1924 Patent

By 1924, Magie’s 1904 patent had expired, and so too had her exclusivity rights over “The Landlord’s Game.” However, in 1924, Magie obtained a patent on a revision of the game. This may be confusing in light of the novelty requirement discussed above.

Magie was able to obtain the 1924 patent on the revision of her game because she added new components. By modifying and improving her invention, Magie was able to obtain a new patent because this invention was not identical to what existed before. The patent office also did not think it was obvious based on her prior patent. So, she obtained a new patent term to protect this new invention, even though it was clearly inspired by the original version. The 1924 patent only barred others from making the newly patented game, and did not prevent anyone from making the game covered by the expired 1904 patent.

Copies Emerge

Magie again struggled to market her updated invention and did not have commercial success. However, the game did gain some traction among economy professors, and students that played the game in class began to copy Magie’s invention. These copies likely infringed Magie’s 1924 patent because they were made before the patent’s expiration and allegedly contained all of the game’s protected elements. However, a granted patent does not come with automatic enforcement. In other words, enforcement is the complete responsibility of the patent owner.

To be able to enforce one’s rights, one must first be aware of a violation that renders such enforcement necessary. This can be especially difficult when a patented invention is being made and used in private homes, as was the case here. If the copies of the game were more public such that Magie was aware of them, she would have had an easier time enforcing her patent rights. However, enforcement of rights also requires resources that may not have been available to Magie at the time.

Additionally, the homemade copies frequently included customizations to street names and property names reflect their own neighborhoods and cities, as well as changes to the rules. Patent infringement does not occur unless every single element of the claimed invention is present. For example, if a patent covers 4 elements and a product only copies 3, the product does not infringe the patent. These modifications in the copies therefore may have taken them out of the scope of Magie’s patent if they lacked elements of her patented game.

Charles Darrow’s 1935 Patent

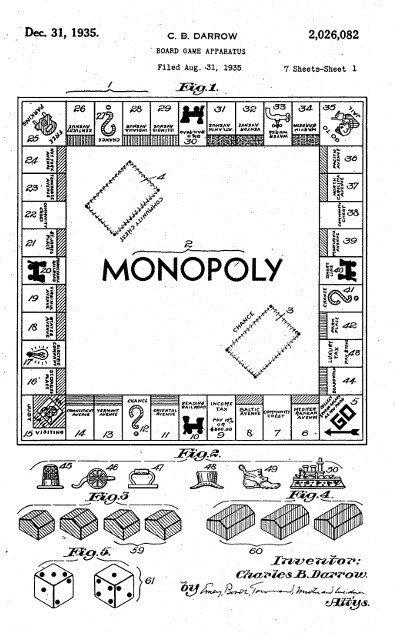

Charles Darrow was one of the people to make his own homemade copy of “The Landlord’s Game.” Darrow was unemployed during the Great Depression, and he initially played his version of the game with his friends before eventually selling the game as his own. Darrow was even able to receive his own patent in 1935 for his version of the game, which included many of the classic images and names of modern-day monopoly. He eventually sold the game to Parker Brothers in 1935, and it became very popular.

Despite being based off of Magie’s game, Darrow made sufficient changes which allowed his invention to meet patentability requirements. He color-coded the properties and deeds, and added new design elements such as the railroads, utilities, and question mark spaces on the board. The rules of Darrow’s version of the game also differed from Magie’s. Instead of having two sets of rules, the goal for all players was to create a monopoly. These differences allowed Darrow to patent a game that was very clearly closely based off of Magie’s invention, because these changes met the new and non-obvious standards.

Darrow initially lied to Parker Brothers about where he got the idea for Monopoly. However, the Parker Brothers later discovered the truth about Magie and her 1924 patent – which was still active at the time of the Parker Brother’s purchase. George Parker then met with Magie and told her they wanted to sell her board game, and she agreed to sell them her patent for $500, without royalties. Monopoly went on to become an even bigger success, with Darrow listed as the inventor on the monopoly box, in addition to his fabricated story about how he invented the game while “tinkering around in his basement.” Magie’s contributions were then lost to history – until a trademark dispute in the 1970s revealed the truth.

The Power of Trademarks

Trademarks are another form of IP, but they differ greatly from patents. Trademark law generally relates to brand protection. A trademark can be a word, symbol, or device that serves to distinguish the source of a product or service. Unlike patents, trademark protection can last indefinitely as long as the mark remains in use and continues to meet the requirements.

The Parker Brothers registered a trademark for the name “Monopoly” in 1936. In 1973, an economics professor named Ralph Anspach released a board game called “Anti-Monopoly.” Because that name is similar to the Parker Brothers’ mark, they filed suit against Anspach for trademark infringement. Trademark infringement is unauthorized use of a valid trademark on goods or services in a manner that is likely to cause confusion about the source of the goods or services. Here, the Parker Brothers were alleging that Anspach’s game being named “Anti-Monopoly” was likely to cause confusion in consumers, which might lead them to falsely believe “Anti-Monopoly” was being sold by Parker Brothers themselves.

The infringement battle that followed led Anspach to uncover the truth: versions of the Monopoly board game had existed long before Darrow claimed he invented it. That discovery was important because the Parker Brother’s claim to exclusive trademark rights could be called into question. Uncovering the truth also allowed Anspach to center Magie as the originator of the idea for the board game she originally invented and named “The Landlord’s Game.”

Conclusion

This story highlights how important it is for creators to recognize the different types of IP they potentially have in their works so they can use various mechanisms to protect their rights. Patents are an important form of IP protection, but they are limited. Though a patent grants an inventor exclusive rights, these rights do not include the right of recognition – particularly after the patent’s expiration. Trademarks also don’t explicitly guarantee such a right, but they do have the advantage of potentially indefinite terms of protection. A successful marketing and potential licensing strategy may have helped Magie remain in the narrative, as well as allowed her to profit from the success of her idea.

When Lizzie Magie patented her invention, she was a pioneer in the field of female inventors. She deserves recognition for her invention, which lives on today as the third best-selling board game of all time. Female inventors have long been overlooked, and still only make up a fraction of total inventors that receive patents. For an in-depth view of this issue for inventors today, see “Girls Just Want to Have Patent Rights,” by Maris Medina.

Lexi Shoup

Associate Blogger

Loyola University Chicago School of Law, J.D. 2026