A primer on the immoral or offensive bar to trademark registration

Trademarks are all around us—from the Apple symbol emblazoned on a MacBook to a “Loyola Chicago” logo printed on a sweatshirt. (Spot three trademarks in that sentence!) Trademarks exist across different industries and evoke different things to a consumer. However, all trademarks serve an essential purpose: to identify and distinguish a good or service in commerce from others’ goods and services.

What is a Trademark?

Trademarks include words, symbols, or “devices” (or a combination of these) that serve as specific source identifiers to a product or service in commerce. This helps consumers quickly identify the source and minimize confusion in the marketplace. A valid trademark enables companies to distinguish their goods or services in the marketplace. To maintain a valid trademark, a trademark owner must continuously use the mark in commerce, and it must remain distinctive. For additional legal benefits, someone can seek official registration with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO).

Supreme Court cases like Matal v. Tam and Iancu v. Brunetti illustrate how trademark registration can involve interesting and sometimes controversial issues. But first, let’s talk about the benefits of trademark registration.

Trademark Registration: How Does it Work and Why Do It?

An unregistered trademark is at a disadvantage in legal disputes. The unregistered trademark does not have any presumption of validity in legal disputes. So, the mark owner would need to establish the basics of why there is a trademark, including that it was used in commerce, and why it is distinctive in the marketplace. In addition, the owner of an unregistered mark may only be able to stop subsequent use of the mark in the specific geographic area in which the business operates.

Federally registered marks receive an arsenal of legal protection and benefits that are not available to unregistered marks. For one, when a trademark owner wants to bring a lawsuit against another for allegedly violating their mark, a federally registered trademark is presumed valid. This helps streamline their case.

Registration also provides constructive notice of ownership nationwide. In lawsuits, this is helpful for trademark owners since other companies and people are presumed to be aware of the trademark. This benefits trademark owners by preventing infringers from claiming they adopted a similar mark in good faith and strengthening the owner’s enforcement rights in legal disputes.

And registration can bring financial rewards. Federally registered marks are given enhanced remedies like statutory damages and attorney’s fees in trademark infringement suits.

The owner of a federally registered mark can also stop the importation of an infringing product at the border. Federal registration allows an owner to register the mark with the U.S. Customs and Border Patrol.

Given all these benefits, why wouldn’t everyone register? One reason is that registration may not be possible. Federal registration of a mark comes with a few requirements:

- The mark must be on goods or services used in commerce

- The mark must be distinctive and nonfunctional (it cannot include useful or necessary characteristics of the good)

- The mark must not be statutorily barred.

This blog focuses on that last prong: the statutory bars to trademark registration.

What are Subject Matter Bars?

The third requirement for registration includes subject matter bars outlined in the Lanham Act. These bars prohibit federal registration of certain types of marks. What are some examples? One bar is the flag of any state or country. Another is the name or signature of a living individual without their consent.

One of these bars, called the “disparagement clause,” intersected with First Amendment law. The clause restricted trademark registration that consisted of “immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter; or matter which may disparage” persons alive or dead. These restrictions led to legal challenges from trademark applicants who argued that denying registration based on moral judgments violated their First Amendment rights. Luckily for many, this bar no longer exists thanks to the Supreme Court’s decisions in Matal v. Tam and Iancu v. Brunetti.

Matal Court Strikes the Disparagement Clause

Until Matal v. Tam was decided in 2017, the “disparagement clause” was good law.

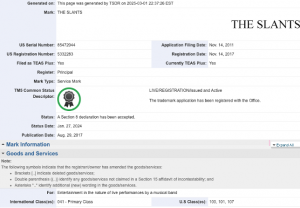

Decided in 2017, Matal v. Tam was a seminal case for trademark registration because it declared the disparagement clause unconstitutional. In Matal, the lead singer of a band called “The Slants” applied to register the band name as a trademark. The singer, Simon Tam, explained that the band name reclaims the derogatory term used against Asians, ultimately “drain[ing] its denigrating force” as a slur.

The USPTO initially rejected the registration and Tam appealed to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB). After losing there, Tam appealed to the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals, which found for Tam. Ultimately, this case reached the Supreme Court. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court found that the disparagement clause violated the First Amendment as a form of viewpoint discrimination.

Before Matal v. Tam, the disparagement clause was the legal foundation for cancelling trademark registration for the Washington Redskins in 2015. The TTAB and a federal district court found that the mark may be disparaging to Native Americans. Even earlier, in 1959, the TTAB refused to register a proposed mark “SENUSSI” for cigarettes. It held that the proposed mark is the name of a Muslim sect that forbids the use of cigarettes and thus would be “an affront to such persons and tends to disparage their beliefs.”

Now, because of Matal, marks that might have once been deemed as disparaging of people alive or dead are now eligible for registration. Of course, they need to meet other requirements too, such as distinctiveness and use in commerce.

What does Matal’s decision mean?

Matal had an immediate impact in trademark registration litigation. Just 10 days after the decision, Native American advocacy groups and the Justice Department (DOJ) abandoned their legal battle in federal appeals court. The case was against Pro-Football, Inc. which owned the Washington Redskins marks. The advocacy groups and DOJ no longer had strong legal grounds, even though they had won in lower courts.

The Court doubled down 2 years later in Iancu v. Brunetti. This time, it found that the Lanham Act’s prohibition on registering “immoral” or “scandalous” trademarks violated the First Amendment. The Court held that these bars similarly exercised viewpoint discrimination as the now-defunct disparagement clause. In Iancu, the respondent sought to register the trademark “FUCT” for his clothing line. This decision dealt another blow to the disparagement clause. The Court pointed out that the PTO has rejected drug-related marks for being “scandalous.” For example, it rejected a “YOU CAN’T SPELL HEALTHCARE WITHOUT THC” mark for pain relief medication. Iancu opens up registration eligibility for marks that might have been deemed immoral or scandalous like curse words.

How has Matal and Iancu Changed the Trademark Registration Game?

If you’re keeping track, here’s what is no longer a valid subject matter bar: the disparagement clause and the bar for “immoral” and “scandalous” marks.

There are some trademarks that can now be registered even if the disparagement clause once barred registration. There’s the Washington Redskins, a once-contested mark for the D.C.-area football team. There are a handful of Redskins marks for use in things like trading cards. Though, the team is now called the Washington Commanders due to the same community pressures that inspired litigation in the first place. There’s also Slant’d, an Asian American magazine that reimagines accessible publishing for Asian Americans. And you guessed it—FUCT—for the fashion label.

It is difficult to show through numbers how Matal and Iancu have impacted the number of trademark registrations, but some groups have tried. Reuters reported a month after Matal, at least nine applications using “racially charged words and symbols for their products” like the swastika were filed. But if you look in the USPTO’s trademark search, there are no approved swastika trademarks. In 2020, Financial Poise noted that most applications for “arguably disparaging trademarks seem to be similar” to Matal. It says that these cases are brought forth by marginalized groups that want to reclaim a term.

Groups like The Slants now can reclaim once harmful language into something empowering and enjoy all of the great legal protections from the USPTO.

Maris Medina

Senior Editor

Loyola University Chicago School of Law, J.D. 2025