When two NFL quarterbacks battle for control, fans typically expect a showdown on the field. But what happens when the competition moves from the gridiron to the courtroom?

The trademark dispute between Troy Aikman and Lamar Jackson offers a fascinating glimpse into the world of intellectual property law, where athletes strive to protect their brands through trademarks. Whether you’re a Ravens fan, a Cowboys supporter, or an intellectual property enthusiast, this case illustrates the intersection of branding, identity, and legal conflict.

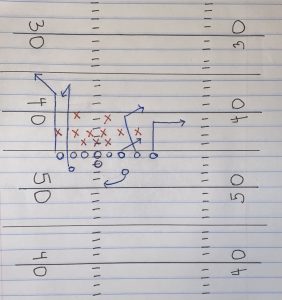

Consider this a playbook to understanding the legal game behind the “8.”

Deb8 Over the 8

Troy Aikman, NFL Hall of Fame quarterback, played twelve seasons for the Dallas Cowboys and wore the number 8 his entire career. In May 2023, Aikman and his company, FL101, Inc., filed a trademark application (serial no. 97931236) for the word “eight” to be used on clothing associated with his name and brands.

Another quarterback, and likely future Hall of Famer himself, Lamar Jackson, was not pleased to hear this news. Jackson has played in the League for the Baltimore Ravens for seven years and counting, and he too wears number 8 on the field. Jackson built his own brand around the number and holds three registered marks related to the number “8.”

In May 2022, Jackson registered “You 8 Yet?” for his restaurant Play Action Soul Food and More! located in his hometown of Pompano Beach, Florida. Earlier in May 2019, Jackson registered “2018 Era 8 by Lamar Jackson 2018” and “Era 8” for his clothing line, Era 8 Apparel.

In July 2024, Jackson filed an opposition action against Aikman’s trademark application, arguing that Aikman’s use of “eight” could confuse consumers due to Jackson’s prior use of similar marks in similar markets.

To understand what the opposition action is and what it may mean for Aikman, let’s break down the world of trademarks, registration, and the opposition process.

The X’s and O’s of Trademark Law

What is a trademark and what does it do?

A trademark is any word, name, symbol, device, or combination thereof that identifies one’s goods or services. Trademarks help consumers recognize brands and foster trust in the quality of the goods or services they provide. Trademarks owners have the right to use their mark and they are protected against unauthorized use by others that is likely to cause confusion amongst consumers.

While trademark owners do not need to register their marks to enforce their rights against unauthorized users, registration confers many benefits. Registering a trademark provides constructive notice to others of the owner’s rights—in other words, people are presumed to have done their research. Registration also establishes a presumption of validity, making it easier to sue wrongdoers anywhere in the U.S.

Without registration, mark owners can still own a valid trademark used with a good or service. Thus, they can still sue others for using a similar mark that causes confusion as to the source of the goods or services.

The Process of Trademark Registration

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) reviews trademark applications and approves marks that are distinctive enough to identify the source of goods or services in the eyes of consumers if there is also no additional statutory bar.

In reviewing the application, the USPTO determines if the mark is distinctive, and then whether the application conflicts with an existing mark. Distinctiveness is a spectrum where some marks are inherently distinctive and identify the source of a particular good or service against others in the marketplace from their first day in use; those marks are categorized as fanciful, arbitrary, or suggestive. Descriptive marks are not inherently distinctive because they describe a characteristic of the good or service and require proof of “secondary meaning”––consumer association of the mark with the source––to be valid. Generic words are never valid because they are common for a class of goods or services (i.e., “clock” for timepieces).

If the USPTO finds no issues with an application, others can still oppose the mark’s registration. When the USPTO approves a mark, it is published in the Trademark Official Gazette, a collection of pending marks. Within 30 days, any third-party who believes they will be harmed by the registration can object to the pending trademark application by filing an opposition action.

Common grounds for opposition include descriptiveness, the mark lacks distinctiveness; dilution, the applied-for mark may weaken the distinctiveness of an existing AND FAMOUS mark; and most frequently, likelihood of confusion, the applied-for mark is too similar to an existing mark thus creating likely consumer confusion.

Likelihood of Confusion

Likelihood of confusion measures whether consumers would mistakenly believe that goods or services from different sources are connected to one another. The same multi-factor test is used to analyze likelihood of confusion in both opposition and infringement proceedings. Courts, including the TTAB, assess factors such as: (1) strength of the opposer/plaintiff’s mark––how distinctive and well-known it is, (2) similarity of the marks, (3) relatedness of the goods or services and manner of marketing, (4) whether the alleged infringer intended to use a similar mark to cause confusion, (5) the degree of care exercised by consumers in differentiating the marks, and (6) evidence of actual confusion.

Like many who oppose trademark applications, Jackson’s grounds for opposition were based in likelihood of confusion.

Opposition vs. Infringement

Even though opposition and infringement may use the same likelihood of confusion test, the possible outcomes are quite different. A successful opposition action prevents trademark registration but does not bar the applicant from using the mark. In such a case, the registrant forfeits the benefits of registration and remains vulnerable to later litigation, including infringement claims by the opposer or others.

In contrast, a trademark infringement lawsuit––which can also follow a failed opposition action––seeks to prohibit the defendant’s use of the mark in commerce. Trademark infringement suits carry steep penalties, including possible injunctions preventing the defendant from using the mark on goods or services in commerce. To succeed, the plaintiff must prove the mark’s validity, the defendant’s use of the mark in commerce, and that the defendant’s use is likely to cause consumer confusion—returning to the likelihood of confusion test similarly used during opposition proceedings.

With these principles in mind, let’s break down how the legal battle over “eight” may play out on the field.

Play-by-Play Breakdown of the “8”

Who’s right and who’s wrong? Who will prevail in this legal battle?

Likelihood of Confusion Test

In the case of Aikman’s application for “eight,” Jackson’s opposition centers on the likelihood of confusion. In assessing their likelihood of confusion, the similarity of the two marks, the relatedness of the goods, and the strength of Jackson’s mark appear most relevant (factors 1-3 above).

Similarity of the Marks

Looking at the factors, Jackson may argue the marks are too similar (factor 2 above). When evaluating the similarity of the marks, the focus is on their appearance, sound, and meaning.

While both Jackson’s and Aikman’s marks involve the number “8,” there are notable differences which may favor Aikman. Jackson’s marks (“You 8 Yet?” and “Era 8”) include additional elements—a playful dining pun and a reference to his athletic career—that provide distinct contexts beyond the numeral. In contrast, Aikman’s “eight” is a standalone term. Thus, the marks are arguably dissimilar in sight as the overlap of “8” is the only commonality.

Though both quarterbacks use “8” in their marks, the meaning of each mark is not the same. Jackson’s “You 8 yet?” is meant to ask the question as to whether someone is hungry, as a pun in reference to “ate” in the context of his restaurant. In his “Era 8” mark, the meaning refers to the legacy of Jackson’s era while wearing the number “8” on the football field.

Comparably, in Aikman’s “8” the meaning inherently refers to the numeral, one more than seven. However, like Jackson, Aikman also wore the number 8 on the field and his mark’s meaning alludes to his identity wearing “8” for the Cowboys. Thus, there is some overlap in meaning with Aikman’s “8” and Jackson’s “Era 8,” especially in the context of clothing and how both marks will appear side-by-side in the marketplace.

From an auditory perspective, while the “8” is pronounced the same in both marks, the marks sound very different when Jackson’s are read aloud in their entirety. The distinct contexts and surrounding words in Jackson’s marks differentiate them further, so that the marks are dissimilar in sound.

Thus, the marks are not likely to be confused when analyzed holistically, considering their different visual, auditory, and conceptual frameworks.

Relatedness of Goods and Marketing

Additionally, Jackson appears to have a strong case when examining the overlap in markets and similarity of the goods (factor 3 above). Jackson already uses both of his “Era 8” and “You 8 yet?” marks on athletic bags and clothing, such as sweatshirts, t-shirts, hats, jackets, and accessories available for sale on his website. According to his trademark application, Aikman also intends to use his mark on clothing. The overlap in the clothing industry is a substantial similarity of goods, which weighs in favor of confusion for Jackson.

Strengths of the Plaintiff/Opposer’s Mark

The strength of Jackson’s marks (factor 1) lies in their inherent distinctiveness, secondary meaning, and the connection to their respective goods. “Era 8” is inherently arbitrary for clothing. The term “Era” does not describe or suggest any qualities of apparel, and its combination with “8” creates a distinctive brand identifier tied to Jackson’s legacy. This distinctiveness is reinforced by its use on merchandise like bags, t-shirts, and hats, which are associated directly with Jackson’s personal brand.

“You 8 Yet?” is suggestive, leveraging a pun on “eight” and “ate” to reference dining, aligning with the restaurant’s purpose. This playful phrasing makes the mark contextually relevant, strengthening its connection to Jackson’s brand.

Both marks incorporate creative elements beyond the numeral “8,” enhancing their distinctiveness and strengthening their function as unique identifiers of Jackson’s brand. Their strength in conception and the marketplace weigh in favor of Jackson.

Sophistication of Consumers

The sophistication of consumers (factor 5 above) may vary depending on the target audience. For fans of Jackson and Aikman, there is an argument that these consumers are more discerning in their buying choices and purchase goods tied to their preferred athlete’s identity. Aikman’s Hall of Fame legacy appeals to Dallas Cowboy fans and nostalgia-drive consumers, while Jackson’s marks target a younger, active fanbase aligned with his current career. Fans are likely to pay closer attention to branding and identity, reducing the likelihood of confusion between the marks.

However, this level of sophistication may not apply to all consumers. For individuals less familiar with professional football or the athletes’ personal brands, the distinction between the marks is likely not obvious. For instance, a casual consumer might not immediately associate “Era 8” with Jackson’s athletic career or recognize Aikman’s use of “eight” as part of his legacy branding.

By acknowledging that fan consumers may demonstrate greater sophistication while non-fans may lack the same level of brand awareness, this factor introduces nuance to the likelihood of confusion analysis. Ultimately, the potential for confusion here may hinge on whether the goods are marketed specifically to fans or to a broader audience.

Furthermore, it appears that Aikman has no bad intent to cause confusion with Jackson (factor 4 above), but rather his marks are tied to his own personal brand.

Balancing the Factors

The likelihood of confusion is determining by balancing several factors, with the similarity of the marks, the strength of Jackson’s marks, and the relatedness of the goods being particularly relevant here. While both parties use the number “8” as a central element, Jackson’s marks are more distinctive due to their creative phrasing and established association with his personal brand. The overlap in the goods—clothing—also weighs in Jackson’s favor, as both parties target similar markets and consumers.

However, Aikman may argue that the simplicity of his “eight” mark, combined with the context-specific nature of its use, reduces the likelihood of confusion. Fans of each athlete may also exercise greater care in differentiating goods tied to their preferred athlete, further mitigating confusion.

Ultimately, while Jackson’s marks are strong and their established use in similar markets bolsters his case, the TTAB’s decision will likely hinge on the overall likelihood of consumer confusion. Even though the marks are not identical, their similarities, particularly in shared markets, could tip the balance in Jackson’s favor.

In this match-up, the likelihood of confusion functions as the referee, calling fouls and throwing flags on branding plays that mislead consumers. While Jackson and Aikman may run different plays than those called in the huddle, their possible arguments appear to be solid strategies to advance the ball in their favor.

The Final Whistle

Even if Jackson’s opposition is successful, Aikman can still use “eight” in commerce, though he would lose the benefits of federal registration. In that scenario, if Jackson is still unsatisfied and believes Aikman’s use in the same geographical regions is likely to cause confusion amongst consumers, he could file a trademark infringement suit against Aikman.

Conversely, if the opposition fails, Jackson can still pursue a trademark infringement suit, where the same confusion factors would apply, but the stakes—including the possibility of an injunction—would be higher.

This legal battle showcases how trademarks are more than just symbols; they represent identity, reputation, and economic value. As Aikman and Jackson duel in this trademark arena, one thing is certain: the intersection of sports and intellectual property law has fans—and legal professionals—on the edge of their seats.

Taylor Lores

Associate Blogger

Loyola University Chicago School of Law, J.D. 2026