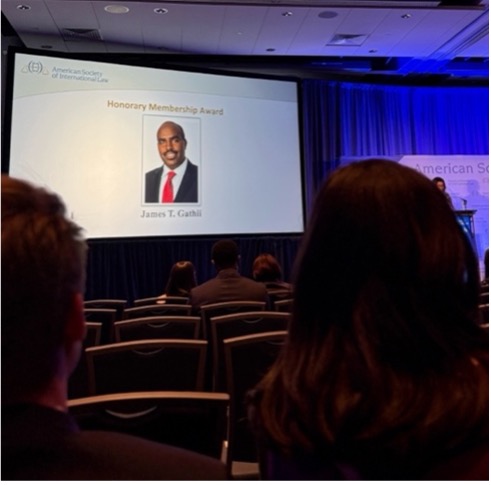

This past April, I attended the 119th Annual Meeting of the American Society of International Law (ASIL) in Washington, D.C. where Loyola’s Wing-Tat Lee Chair of International Law, Professor James Thuo Gathii, was honored with The Honorary Member Award. Heading into this meeting, I was looking forward to hearing the Grotius Lecture by former UN Special Rapporteur, E. Tendayi Achiume, on contemporary forms of racism.

However, I became elated when I learned the newly formed Intellectual Property Interest Group (IPIG) was hosting two panels discussing the intersection of intellectual property (IP) and international law!

The Panel

I did not hesitate in adding each IP panel to my schedule. I was particularly fascinated by the second panel, “Intellectual Property Law in Transition: African and Asian Perspectives.” This panel set out to discuss whether traditional knowledge, to be explained more below, can be protected by current tenets of IP law.

Members of the panel included Janewa Osei-Tutu, Srividhya Raghavan, and Chidi Oguamanam. The mediator, Ruth Okediji, laid the foundation that 35 years ago ASIL members would never have dreamed of an IP and international law panel. In fact, panelists commented that intellectual property has typically not been a mainstream issue at international law conferences. She said that it was COVID-19 and its effects on access to medicine that prompted more attention to intellectual property on an international scale by ASIL. At that moment, I knew I was in for a groundbreaking session.

The Conversation

For starters, I learned about the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property of 1995 (TRIPS Agreement). This is the governing treaty that requires certain domestic laws regarding intellectual property for World Trade Organization (WTO) member countries. The current critique among international intellectual property practitioners is that the TRIPS Agreement largely reflects the IP rules of the Global North. This critique and the debate on whether traditional knowledge (TK) could be adequately protected under TRIPS standards prompted the panel’s discussion.

The panel described traditional knowledge as being cultural traditions that are typically passed down orally in cultural groups, communities, or often, indigenous peoples. An example of this offered in the panel included medicinal usages from a country’s native plants. Professor Osei-Tutu included yoga as an example of Indian traditional knowledge in prior work, “What Do Traditional Knowledge and Traditional Cultural Expressions Have to Do with Intellectual Property Rights.” Prior to this panel, I would have never realized there are barriers to protecting this form of culture. I learned that a native plant, such as one used for medicinal purposes, cannot be protected by a patent due to lack of novelty. This patentability requirement bars protection because the plant has been used for a long time without patent protection and thus is no longer considered new. The panel prompted discussion of what can protect this type of knowledge, creativity, or innovation?

A House Divided

Professor Oguamanam stated that “developing countries and indigenous communities were not in the room when discussions about intellectual property rights were being debated.” Therefore, there is an overall lack of equity in the space, making it tough for traditional knowledge to ever receive adequate recognition for rights within the current TRIPS system. Oguamanam says that African countries specifically were given a mere “promise” from the TRIPS Agreement, and it never worked for their world views, value systems, and importantly, their traditional knowledge.

The other side of the panel argued that current IP systems still have some good to serve for traditional knowledge, cultural expressions, and things of the like, such that some protection rights can work with some room for improvement. Professor Osei-Tutu offered that instead of writing off the current IP system under the TRIPS Agreement as inoperable, the system should instead be expanded to cover protections for traditional knowledge. This argument was rationalized in that if there are no rights recognized for cultures’ traditional knowledge, it is tougher to stop appropriation with modern inventions being patented (to be discussed further below).

Emerging Solutions for the Preservation of TK

Professor Raghavan shifted the conversation to India’s solution which appears to balance the current IP system and traditional knowledge expansion in practice. India has pushed the protection of its information, including traditional knowledge, by creating their own database! India’s Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) has become an effective way for the country to defend its traditional knowledge in at least patent law, by ensuring its TK can qualify as prior art, which refers to something that came before an invention that could be relied on to deny patent rights. The database helps ensure TK is known to those who evaluate patent applications in India, ensuring it is public and documented. This prevents biopiracy, the granting of patents that are based on appropriated TK.

The TKDL database is a game changer! Let me tell you why by connecting the dots to IP law concepts I have learned in Professor Cynthia Ho’s Intellectual Property course. Before the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA) was enacted in 2013, knowledge in public use outside the US was not considered valid prior art even though things in writing outside the US did count. Often traditional knowledge is not documented due to it only being enshrined in oral history. So, pre-AIA, TK was often disqualified from constituting a prior art reference with respect to US patents. This meant that another applicant could possibly obtain a patent based on a country’s TK because the TK wasn’t considered when evaluating the patent application for novelty or non-obviousness. Although the US today considers undocumented information outside the US to be prior art, patent examiners may still be unaware of such information. But, the database in India helps with that. So, even though communities may struggle getting their traditional knowledge to rise to protection status in the current IP system, they can at least defend themselves against cultural appropriation with databases that ensure traditional knowledge is accounted for and more readily recognized as prior art.

International IP has come a long way, but there is still much more to go. Panelists praised progress made in protecting TK, such as the new World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Treaty on Intellectual Property, Genetic Resources and Associated Traditional Knowledge (GRATK). The GRATK does not require a database, but for member countries, it will require that patent applicants disclose whether inventions are based on traditional knowledge or genetic resources. The Treaty is intended to ensure patents are not improperly granted on inventions that are actually not new because they are known in traditional knowledge.

Overall, the panel was full of scholastic critiques, but it reached common ground in prioritizing the advancement of indigenous and cultural community justice in intellectual property. TK databases and conversations like these seem to be a step in the right direction.

The Conclusion

In reflection, I am thankful for the opportunity to attend ASIL’s Annual Meeting to expand my scholastic and cultural understanding. There is so much more to intellectual property than a copyrighted song lyric or a trademark. It is truly such a nuanced discipline. This one April weekend in D.C. left me wanting to explore the panelists’ thoughts back at Loyola. Along with Professor Ho’s Intellectual Property course, I am taking Professor Gathii’s International Trade Law course this fall. In International Trade Law, I am writing my final paper on (you guessed it) the intersection of international law and intellectual property! I pledge to continue learning IP through a social justice and equitable lens.

Kendall Henry

Assistant Blogger

Loyola University Chicago School of Law, J.D. 2027