By: Brenton Villasenor

Even if you can, does it mean you should? Many religious school advocates may soon have to answer this question. The Supreme Court’s Carson v. Makin decision in June 2022 was perhaps one of the more significant outcomes of the last session. The dispute was over Maine’s tuition assistance program that would pay for a student’s private school tuition if they lived in an area that lacked a public school option. The catch was that the school could not have religious instruction. Maine was one of 38 states to have adopted a “Blaine Amendment” that expressly prohibited state funding for religious schools.

The Supreme Court in a 6-3 decision ruled that the Maine tuition assistance program denying funding to religious schools violated the Free Expression Clause of the First Amendment of the Constitution. In the opinion, the majority ruled that Maine’s “no-aid provision” preventing religious institutions from partaking in tuition assistance programs discriminated based on religion. In doing so, the Court may have opened the door to religious-based charter schools.

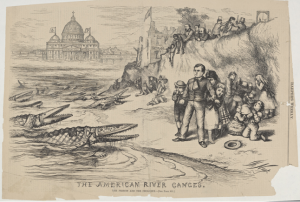

Thomas Nast political cartoon depicting a public school teacher protecting the children from the Catholic bishops invading onto land. (1872). New York Public Library Digital Collections

The issue in Carson centered around Maine’s Blaine Amendment. The term “Blaine Amendment” was coined after James Blaine, a Congressman and Speaker of the House who introduced an amendment to the United States Constitution in 1975 that would deny state funding for religious schools. The bill was prompted during a time of extreme anti-immigrant, especially anti-Catholic sentiment. Although the bill failed at the federal level, variations of it were adopted into state constitutions. At the time, public schools taught Protestant prayers and read from the Protestant Bible. For example, in 1838, Pennsylvania law mandated that the Protestant King James Bible be taught in schools. In 1963, the Supreme Court eventually ruled that Bibles could not be taught in schools.

As Catholics came into the country and attended public schools, they were forced to adopt a Protestant worldview if they wanted to further their education. Even so, they were subject to ridicule and persecution. As a result, Catholics established their own schooling system. Catholic school enrollment grew steadily throughout the 20th century to its peak at 4.5 million in the 1960s. It has declined by over 50% since then.

Student Reading. Photo from Pexels.

How Did We Get Here?

The First Amendment of the Constitution states: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” There exists a fierce debate as to its limits. On one hand, the Establishment clause prohibits the government from recognizing an official religion. On the other, the government cannot prohibit the practice of religion. These two theories have been contested many times in the nation’s highest court.

For decades, the Supreme Court relied on a three-prong test in determining whether a school could receive funding. In 1971, the Supreme Court adopted the so-called Lemon test which required that the law have a secular purpose, have an effect that does not promote or inhibit religion, and must not excessively tangle government and religion. However, in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, the Supreme Court started to move away from this test and ruled that tuition vouchers could go to religious schools. In its decision, the Court focused on the use of the funding being determined based on private choice in ruling that the policy was neutral as it related to the Establishment Clause. Essentially, because this money was going to the parents, the government was not directly funding religious schools. Rather, the parents were exercising their choice to use that money to send their child to a religious school. Thus, the funding came from parental choice, not the government.

In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled Montana’s Blaine Amendment violated the Free Expression clause in Espinoza v. Montana. Similar to the law in Carson, Montana’s no-aid provision prohibited religious schools from receiving government money from the state’s tax credit scholarship program. In the majority opinion, Chief Justice Roberts stated that, “A State need not subsidize private education. But once it does, it may not disqualify a school solely because they are religious.” Like in Espinoza, Maine’s tuition subsidy included private schools, except for those schools with religious affiliation. Thus, the Court in Carson adopted this language in striking down Maine’s Blaine Amendment.

The Current Outlook: Down, but Not Out

Does this mean that all states now need to fund religious and private schools? Not necessarily. The Court’s rule is that a state does not have an obligation to provide funding for private schools, but once it does, it cannot exclude religious schools. That is, a state does not need to pass a law that provides for private school funding in the forms of tuition aid programs. However, if they do pass such a law, the funding must be inclusive of religious schools. Many of these programs come in the form of vouchers and educational savings accounts (ESAs), where parents are given funds towards their child’s education. However, a crucial question is yet to be resolved: does funding for privately-run charter schools trigger an obligation to open the door for religious private schools?

This ruling comes at a crucial time for religious schools. According to data from 2019, private schools served 4.7 million students, 9% of the overall market share. The remaining 91% of students attended public school. Non-Religious private schools enrolled 1.1 million students. Religious schools of various faith traditions accounted for the remaining 3.6 million children. Catholic schools were the largest player in the religious school category, enrolling 1.8 million students.

The COVID pandemic substantially affected enrollment in these schools. Job loss and economic uncertainty made it much more difficult for families to finance a private school education. Catholic school enrollment dropped 6.4%, the largest single-year decline in 50 years. In the Archdiocese of Chicago alone, enrollment dropped 8.4%. Furthermore, over 200 Catholic schools shut down in 2020. These closures disproportionately affected black and low-income communities.

Since the Carson ruling, those numbers have trended upwards. Since the steep decline in 2020, Catholic school enrollment has grown about 4%. This is coupled with the closure of only 44 schools, the fewest in over 20 years. This boost has coincided with a push for educational choice legislation in numerous states. In 2021 alone, 18 states enacted new or expanded existing choice programs. The average scholarship value through one of these programs was $5,400. These programs vary in breadth, with West Virginia’s Hope Scholarship being the most expansive educational savings account program in the country. This momentum has continued in 2023, where 11 state legislatures have introduced bills that would establish new or expand existing educational choice policies. Currently, 26 states have some type of educational choice program. The surge in choice legislation served as a breath of new life for private and religious schools, who now were able to open their doors to more students who otherwise would not have been able to afford it.

The Carson ruling and subsequent wave of legislation has changed the role that many private and religious school advocates play. Supporters of faith-based schools are now empowered to be more active in the policymaking space. Whereas they may have not been involved with the political process before, they have a renewed voice to support legislation that gives them a lifeline and an opportunity to grow.

Students working together in a classroom. Photo from Pexels

What about Charter Schools?

In his dissent in Carson, Justice Breyer raised the concern that the difference between a charter and secular private school would eventually eliminated. Traditionally, the difference between charter and private schools has been this: charter schools are publicly funded, but privately run. Private schools are privately run and privately funded. Breyer introduces the idea that if the State must fund private religious schools, then the difference between the two would become blurred even more. Essentially, in his view, the ruling could open the door for religious charter schools.

Recently, Breyer’s fear has been pushed to the test. On October 23, 2023, the Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board approved a charter contract to St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Charter School. This contentious, yet historic vote made St. Isidore the first religious charter school in the nation. Unsurprisingly, a legal battle ensued.

On June 25, 2024, the Oklahoma Supreme Court issued a 6-3 decision blocking the school from operation, stating its charter status violates state and federal law. The Court ruled that Oklahoma’s Blaine Amendment prohibits the government from using public money for the “benefit or support” of any religious institution. Furthermore, public charter schools in the state are required to be nonsectarian. Therefore, St. Isidore, as a Catholic charter schools was in violation of the Oklahoma Constitution and thus was prohibited from opening.

Despite the Oklahoma’s Supreme Court ruling, the Virtual Charter School Board decided to keep the school’s contract while it figured out its next steps in litigation. Presumably, this means petitioning the U.S. Supreme Court. Based on the Supreme Court’s ruling in Carson and Espinoza, this could mean that this historic legal battle is far from over.

The Complexities of Charter Status

Assuming a world where religious schools were able apply for charter status, should they? Those in religious education would need answer this question: how do we do successfully?

If faith-based schools choose to apply for charter status, they will gain access to public funding for its operations system. Currently, the nationwide average cost per pupil for Catholic elementary schools is $4,480 compared to the public school at $15,004. This money could go a long way in updating resources, increasing teacher salaries, amongst so much more. However, this opportunity would not come without a cost.

Although privately run, charter schools still must follow certain state requirements and admissions procedures. One of these requirements is that the school would then need to eliminate all enrollment requirements. For example, Illinois requires open enrollment in charter schools with a lottery system once the school hits capacity. By transitioning from private to charter, many religious schools may inadvertently put themselves in a position to fail. The current facilities of many older religious schools may not be able to meet the demands of charter school operations.

While charter status may help correct dropping enrollment in religious schools, it is possible that too much growth would be counterproductive. Many religious schools have never had to deal with large class sizes, and thus do not have the infrastructure to accommodate a larger student population. Furthermore, some states require charter schools to generate their own funding to make facility improvements. As many school buildings are outdated, the cost of these upgrades may outweigh the benefits of increased funding. In the inner cities, schools do not have the space to rebuild or expand. Thus, the “growth” would be limited at the cost of taking funds away from instruction.

Religious schools have long enjoyed the ability to limit class sizes to foster a strong sense of community, offer a challenging academic curriculum, and provide a value-based curriculum that builds strong character development. Parents send their children to these because they believe that these schools offer a better, safer learning environment for their child. Currently, about 40% of Catholic schools operate a waiting list. This suggests that the schools willingly sacrifice tuition dollars in order to keep small class sizes, which improve student performance. Studies suggest that 18 students is the ideal number of students in the classroom. Currently, the average religious school class size ranges from 14-18 students compared to 26 students in the public school system. Transitioning to charter status would potentially take religious schools away from the optimal class size, and thus take away from the academic well-being of its students.

My former classroom when I was a Middle School Language Arts teacher at Our Lady of Guadalupe School in Los Angeles, CA.(2020)

Catholic schools have found a sweet spot providing academic excellence over their history. According to the NAEP’s Nation’s Report Card, Catholic school students outperformed public and charter school students in both reading and math. The schools’ smaller class sizes and overall school community allows for easier cohesion and collaboration. When you have a school community that gives parents, students, and faculty a seat at the table, it results in a more welcoming, innovative environment. All members are empowered to play an active role in the child’s education.

A teacher can more readily respond to recognize and respond to the individual needs of the students in a small learning environment. Managing fewer students allows for a more individualized education and curriculum designed specifically for those students in that classroom. When curriculum and rigor reflects the make-up of the students, classroom instruction becomes more effective. Religious schools have set themselves apart by operating in a way that focuses on the child’s education first. For example, in my experience as a Catholic school teacher, my average class size was about 13 students per class. This allowed me to provide individualized attention to each student, without sacrificing significant class instructional time. Furthermore, it allowed me to more easily differentiate lessons to be able to reach the various types of learners in the class. As a result, many of my students experienced significant improvements in their skills.

For over a century, Catholic and other religious schools have put an emphasis on responding to the needs of the community and its children. A major reason they have lasted the test of time is because the community sees value in this model. By abandoning private status to receive the financial benefit of charter status, these schools risk abandoning the very thing that made them successful: tailoring their education to the needs of the student.

At this point in time, religious schools do not have the infrastructure to ensure the same level of rigor and learning experience of a larger school. Providing a high-quality education with smaller class sizes has been the bread and butter for these schools for over a century. A misstep in the transition to charter status could potentially jeopardize that. There is no reason for religious schools to go away from what they have done so well for so long.

While transitioning to charter schools would go a long way in ensuring the longevity of the religious school system, the issue of whether these schools can successfully maintain a high academic record is in doubt. Purely looking at student outcomes and academic success, many religious schools have a good system in place. Because of this, the risks of expanding outweigh the benefits.

Furthermore, the possibility of religious charter schools would likely not move the needle to provide the needed relief to many of these schools. This is mainly because the ability to gain charter status is regulated by statute. In Illinois, for example, state law limits the number of charter schools to 120. Furthermore, charter applications need to be approved by the governing agency. Thus, even if religious charter schools are allowed by federal law, state law could intervene and limit access to start them. Even in New Orleans, where all public schools are charter schools, the districts have the authority to choose which schools to accept into the charter network. Thus, there is no guarantee that states and districts would allow religious schools to operate. Put simply, a state or district can simply not add any charter schools, eliminate charter schools altogether, or limit the number of accepted charter schools per year. Therefore, a favorable outcome in the Oklahoma case will have a very limited effect for the majority of the country as it relates to providing resources and access to religious schools.

Religious school advocates should continue to push legislation for scholarship programs through tax-credit scholarships, vouchers, and educational savings accounts to grow and better serve their students. Increased funding through private school choice programs will give schools the opportunity to grow at a pace that reflects the demands of the community. Over time, these incremental upgrades allow the school to increase enrollment, upgrade infrastructure, and invest in resources based on the needs of its students. Religious schools have built their reputation by putting the needs of the students and community it serves first. The value in this model is worth much more than benefits the charter system provides. Even if you can, doesn’t mean you should.

Brenton Villasenor is a law student at Loyola University of Chicago Law School and wrote this blog post as part of the Education Law and Policy Course.