“They have law for patents?” I asked my friend. He was telling me about his new job as a legal assistant in a patent law firm. Little did I know, patent law would play a significant role in the start of my legal career.

How did that happen, despite knowing nothing about patents? Let me explain.

My Intro to Patent Law

I wanted to work at a law firm after undergrad to see if law school was a worthwhile investment. I accepted a position at a patent law firm and really didn’t know what to expect. All I knew is that we did whatever “patent prosecution” was.

“Prosecution?” I thought to myself. “Isn’t that something that only happens in criminal law?”

One thing I did know for sure is that we worked with a lot of science. Most of the attorneys I worked with had a Ph.D. in fields such as organic chemistry in addition to a law degree. They also had to pass an additional exam often called the “patent bar” to practice before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), The patent bar also required a hard science degree in order to even sit for the exam. As a political science major, “hard” science was not really my thing. So, I initially felt totally out of my element.

What’s the Point of a Patent?

I quickly learned that patent “prosecution” actually has nothing to do with criminal law. It’s actually just a name for the process of how an invention becomes a patent. I also learned that this can be a lengthy process.

It all starts with submitting a patent application to the USPTO. There, a patent examiner, who has knowledge of patent requirements and the science involving the invention, will send the application back with reasons for rejection. This is called an Action, “referring to an action from the patent office. Then we respond, often with proposed amendments to address the examiner’s contentions. This goes back and forth for years (and costs thousands of dollars in filing fees) until the examiner finally decides to issue a “Notice of Allowance.” This notice indicates the application can become a real granted patent (after payment of fees). However, that’s only IF it gets granted. Some applications are rejected no matter how many office actions and responses are exchanged.

The most common type of application I filed was called a “provisional.” Provisional applications are not examined. Instead, it is a way to get your idea on the books before anyone else to help you get a patent later. These cost anywhere from $300 to somewhere in the thousands, depending on the page count. If the client chose to proceed to the examination stage, a different application is filed – and of course – an additional fee is required. Because of the backlog at the USPTO, these applications would often not get a first office action for at least a year.

Patents and Prestige – Changing My Perspective in the Pandemic

As time went on, I started asking more questions about why so many people pursued patents when they took so much effort. I wanted to know how this type of law relates to the greater good. What was the tangible benefit of a patent? After all, weren’t patents just for helping the “big and bad” pharmaceutical companies get more money?

My perspective started to change around Mid-March 2020, due to the global pandemic pushing biomedicine to the front of the news. I became even more curious about how patents played a role in public health. I asked one attorney if the prosecution we had been doing had an impact on vaccine development and he said, “This is why we do what we do.” Many of our clients, some of whom began as startups, had actually been studying coronaviruses and other infectious diseases for years. They relied on investors to continue funding their research, and patents were impressive to those investors.

Suddenly, a field that I thought was entrenched in money and power became more humanized. The late nights preparing and filing applications and response to office actions actually had some indirect impact on mitigating the pandemic and public health across the world. This realization made it all the more difficult to leave my job for law school because I assumed I couldn’t get involved in patent law or intellectual property. My bachelor’s degree in political science wasn’t the type of “science” required to take the patent bar. Although I thought I had closed the door to IP issues, I was wrong.

Discovering IP Law beyond Patents at Loyola

When I started applying to law school, I didn’t expect I’d end up at Loyola University Chicago School of Law, far from my Boston roots. I also didn’t think I’d have any continued interest in intellectual property law because I couldn’t take the patent bar.. Spoiler art: deep dish convinced me to move, and my interest in patents didn’t go away. Plus, I discovered that you only need a science degree if you want to prosecute patents, not to protect them.

At the suggestion of Professor Ho, my first semester Civil Procedure professor who also is the Director of Loyola’s IP Law Program, I decided to join Loyola’s IP Law Society. I began attending networking events with upperclassmen and alumni where I learned that’s there’s more to IP law than just patent prosecution. One event called “Building Brands” was hosted by Loyola alumni Lema Khorshid. At the event, many of her small business clients talked about how meaningful it was for them to have their ideas protected by IP. These protections included things beyond patents such as copyrights and trademarks. I was also pleased to learn that my lack of a science degree was irrelevant to practicing in those areas.

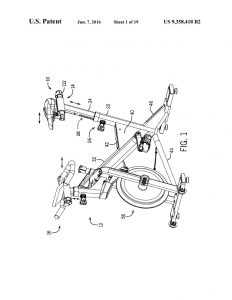

Later in the semester, I had the opportunity to sit in on presentations that Professor Ho’s IP class put together. I was surprised at the nostalgia I felt seeing images of patents again. I was also excited about the diverse array of topics her students chose to discuss. This included patents related to SoulCycle and the unauthorized use of Kylie Jenner’s fictional Kylieverse trademark, and beyond. I’m already starting to think of topics from my own presentation when I hopefully take the class next year.

Ultimately, the unexpected ended up being the wonderful thing about my experience with patent law. I can’t wait to see what else the unexpected will bring during the rest of my time at Loyola and in my legal career.

Maddie Domenichella

Assistant Blogger

Loyola University Chicago School of Law, JD 2024

Incoming IP Law Society President, 2022-23