Welcome, everyone, to the English Department’s revitalized blog! Our teaching, our learning, and our living have never been so disrupted, and our hope is that this place can be a small place for sharing and connection, even as we’re all, as Mary Wollstonecraft would say, “immured in our families, groping in the dark.”

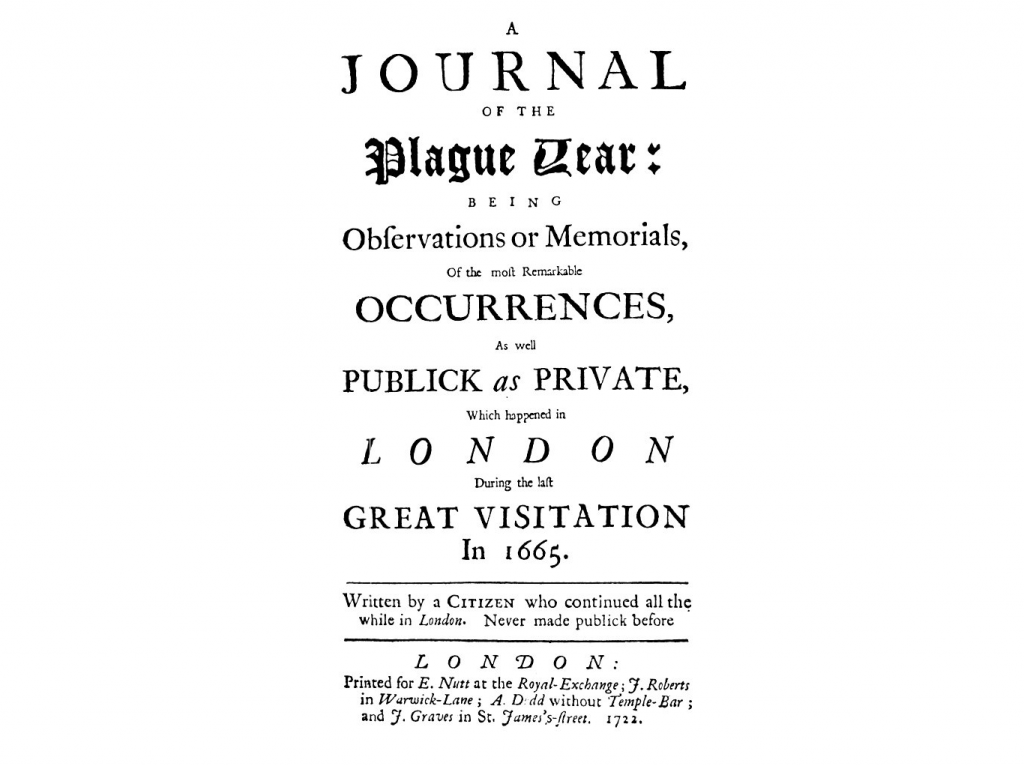

Our idea is that our whole community—students, faculty, staff—might help build this “Journal of a Plague Year”. Teaching from my dining room table this semester has shown me how much I took for granted, and how much I now miss, the casual conversations and connections with students and friends that were the texture of a regular day on campus.

I think we’d all like to know how everyone else is doing, and this blog can be our window into each other’s experiences. We’ll be hosting what any of you would like to share: reports on how you’ve handled quarantine and The Remote University, stories you’d like to give us, poetry, fiction, or anything else that you’ve made in response to COVID, or even just pictures of your quarantine quarters. Send anything you’d like to share with us to me (jcragwall@luc.edu) and Anna Rubenstein (arubenstein1@luc.edu).

I thought I’d start by sharing something I wrote for our graduation ceremony in May. Things were different then: the economy was in more obvious freefall, infection rates were rising rapidly, and my very young children hadn’t seen a playground in months. And at the same time, nothing much has changed, and some things have worsened: a future of two hundred thousand dead would have shocked me during the hardest moments of quarantine. We’re further along now than in May, but I’m not sure where we’re going.

Graduation in the time of COVID (May, 2020)

Thank you all so much for being here. I’m so glad that we’ll have this opportunity—however transformed—to celebrate our students and their extraordinary accomplishments.

I’ll start, confessing that in a moment of weakness, I asked David if we shouldn’t cancel this celebration. I worried that it would be diminished, a “celebration” of small boxes and smaller talking heads, reminding us of what’s been changed, lost, and broken.

I worried that the goofy sanctity of the event wouldn’t survive, and that our students—and their hard work, enormous talent, and courage in adversity—wouldn’t get the celebration they deserve. What I really worried about, though, was that I was diminished.

I remember the moment. In the first week of quarantine, I was hurrying through a pile of papers during my youngest child’s ever-shorter nap. I was trying to critique a student thesis, pen poised over the margins, when it broke over me: this doesn’t matter now.

Maybe this was generosity, not acquiescence, I thought. In the hour of plague and collapse, surely there’s a virtue in accommodating three-quarter-formed theses. But there was a terror in it, too.

It doesn’t matter now—will it ever again? When? Will I be there to see it? Who won’t? And if this thing that we all, student and teacher alike, love so much—being in a room with interesting people, thinking about interesting things—if this thing could cease to matter so quickly, giving way within a week to existential concerns, how much did it ever matter, really?

Last week the Undergraduate Program Directors of all the Humanities departments did an event for accepted students and their parents. The first question was “why should someone study the Humanities”? Our answers were competent: we talked about skills, outcomes, pleasures. We’d done this before.

But our answers felt like archeological shards from a ruin we’d inhabited only days earlier, and still wished we did: where seminars weren’t screens, where jobs for students and their parents still existed, where terror didn’t cage us in our homes, where Moloch and Mammon weren’t demanding us outside as their prey.

Moloch and Mammon, Satan’s princelings, demons of slaughter and profit. Paradise Lost has helped me to figure the evil of this moment.

It’s right there in its title—the poem is never not about loss. It’s especially good at cracking that brittle bravado, masquerading as optimism, of its anti-hero, Satan. All the high-sounding “courage never to submit or yield,” that determination not to be “lost in loss itself,” the final lie that “the mind is its own place”—all this insistence that everything will be okay with enough grit, is the colossal stupidity of someone working hard not to see how irrevocably altered everything is.

So it’s not Satan, but Eve, only Eve, who’s given me something I can give you. At the end of the poem, anticipating cataclysmic exile, Eve turns to Adam, and speaks the last words of any character in the poem:

In mee is no delay; with thee to goe,

Is to stay here; without thee here to stay,

Is to go hence unwilling; thou to mee

Art all things under Heav’n, all places thou.

Eve’s courage is what Satan, Adam, and even Milton’s Messiah never achieve: a courage that isn’t diminished by catastrophe, but diminishes it. It’s a courage of companionship and shared vulnerability, capable of admitting that there’s no safety in the self, in the narcissism that claims to make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven—it’s the people we love who transfigure space and time for us, if we have the strength to let them.

Eve leaves Paradise willingly because she knows that the work of love can make a new one, happier far. But she has another consolation, one especially meaningful for the people gathered virtually together here, today.

Her primal anxiety was always language. Unlike Adam, Eve never speaks on the day of her creation, and can only narrate its trauma long after the fact. She’s the gendered difference that makes the Word of God signify, along with the great chain of masculinities who bask in Its image as their own. She plucks the Fruit in the desperate hope that it might “give elocution to the mute, and teach the tongue not made for speech to speak.”

It doesn’t work. And yet.

Her last words, spoken as her home burns in the wrath of God—her words don’t rhyme, since almost nothing in the poem does. But they do add up to fourteen lines, a math problem even English majors can solve. Eve’s final, and our first, comfort is the sonnet—the original poem, fast after the original sin.

Milton gives Eve the dignity his God never would—she is the one who pursues things unattempted yet in prose or rhime, as the mother of humankind and poetry both. One is the measure of the other.

I’d been worried that crisis is no time for poetry. But poetry was the only thing we carried from the ashes of the Garden. It’s not the thing we give up first; it’s the thing we do first. This thing we all share, the thing we’re brought here to celebrate today—it is, as another poet said, the rock of defense of the human spirit.

After Eve finishes her valediction, Michael ushers the couple to the gates, where they drop some natural tears. But instead of punishment, they are rewarded with a vision of quiet sublimity: “The World was all before them.” Whatever that time before was, it was never part of the “all” that makes up the “World.” A conventional theology would have this be a time of cosmic sadness. For Milton, it’s a somber call to action—a world of choice, duty, and labor, that make Paradise and its loss feel parochial.

Our world will heal. It will heal because we—and especially the students whose grace, intelligence, and determination we’ve come here to celebrate—will heal it. We will make it more just, humane, and righteous. This moment, and its aftermath, will call our students to a heroism of necessity from which I wish, for all the world, I could excuse them. I can only promise them that as they take their solitary way through what comes next, they will do so hand in hand with us.

Jack Cragwall